Contents

MVO Architecture

This little library helps you implement an architecture we’ll call MVO (Model View Observer). MVO is a convenient way to talk about how fore connects architectural layers together, but fore doesn’t really mandate a specific architecture: as long as an architecture has layers, fore style observers can be used to make them reactive. For example, fore style observers are being used in this clean architecture app.

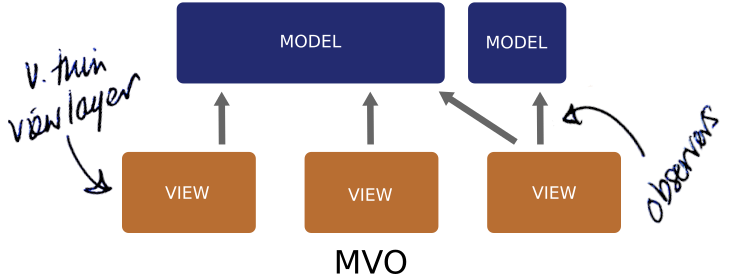

That block diagram above is what MVO looks like (it’s simplified of course, further details below).

By Model we mean the standard definition of a software model, there are no particular restrictions we will put on this model other than it needs to be observable (when it changes, it needs to tell everyone observing it, that it changed) and it needs to expose its state somehow, via quick returning getters, properties or a single immutable state. The model can have application level scope, or it can be a ViewModel - it makes no difference from an MVO perspective.

By View we mean the thinest possible UI layer that holds buttons, text fields, list adapters etc and whose main job is to observe one or more observable models and sync its UI with whatever state the models hold. If you’re going to implement MVO on android you might choose to use an Activity or Fragment class for this purpose, a custom View class, or a Composable.

By Observer we mean the standard definition of the Observable pattern. In MVO, the Views observe the Models. (This has nothing to do with Rx by the way, fore is not an implementation of reactive-streams - very much by design).

For the avoidance of doubt, most non-trivial apps will of course have more layers behind the model layer, typically you’ll have some kind of repository, a networking abstraction etc. There are a few slightly larger, more commercial style app examples to check out: this one takes the MVO structure and applies it to a full clean architecture implementation written in kotlin modules. This one is a more simple MVO implementation written in Kotlin and another in Java (which has a tutorial to go along with it).

In a nutshell this is what we have with MVO:

“Observable Models; Views doing the observing; and some Reactive UI tricks to tie it all together”

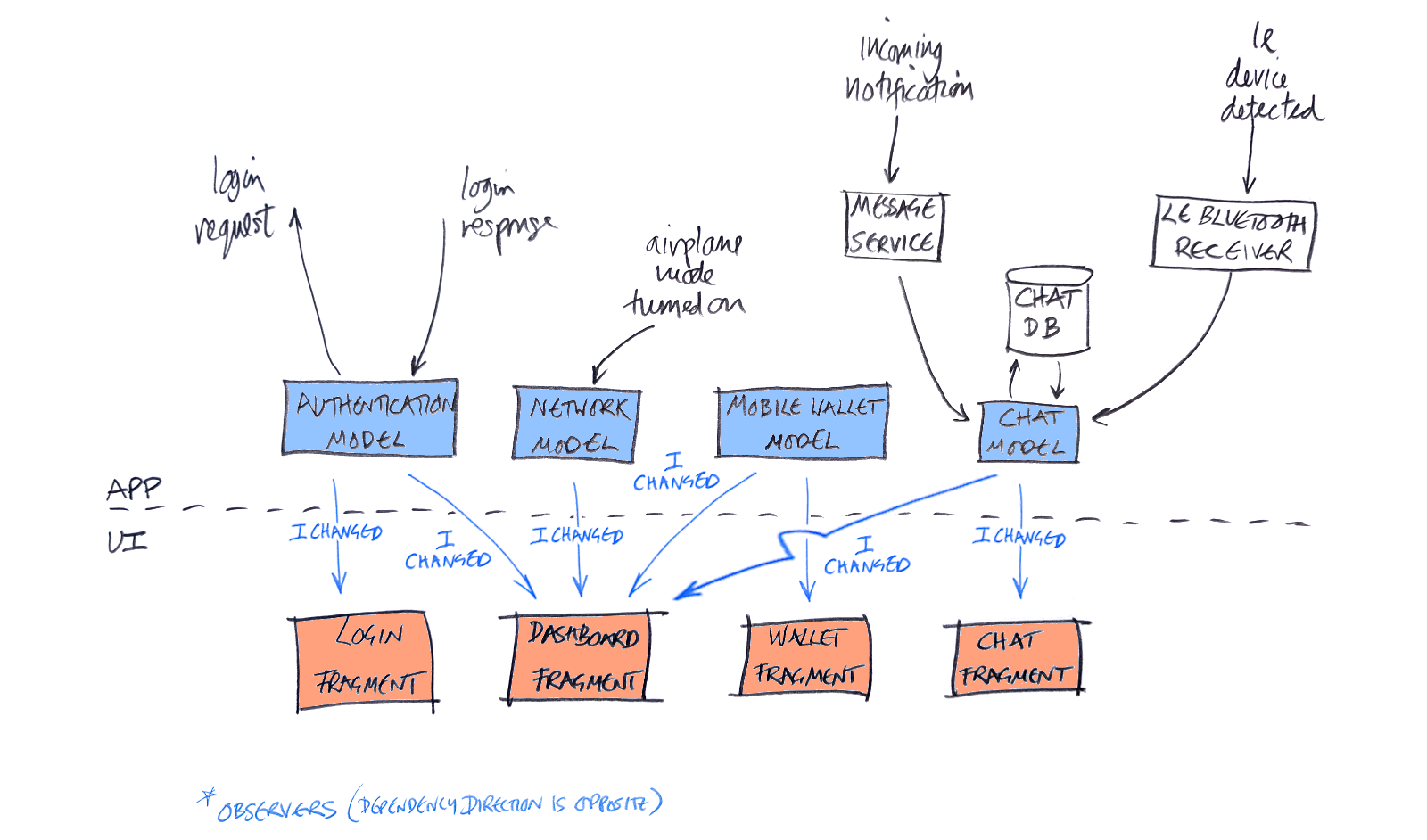

Here’s an example app structure showing some models being observed by fragments in typical MVO style. As discussed below, the dependency arrows point towards the models (i.e. the view layer is aware of the models, the models are not aware of the view layer).

A lot of the time, things happen in an app that do not originate directly from user interaction: incoming notifications, network connectivity changes, Bluetooth LE connections etc. We have to propagate those events to the view layer somehow. Sometimes that is done by locating the current foreground activity / fragment (using ActivityLifecycleCallbacks for example) and then pushing the information to the view layer directly: this is the opposite of a reactive UI. Implementing this with reactive-streams is doable, but not without paying the reactive-streams tax.

MVO’s observable models provide an easy and much less boiler-plate intensive solution: when the models’ state changes, they notify their observers (they don’t need to involve themselves in any view layer considerations at all).

It’s the view layer components job to observe whichever models they are interested in, and synchronize their UI when those models change.

This flow is so lightweight and easy to implement, it’s actually how MVO handles all state changes, including those that are a result of network responses, or actions triggered directly by the user (it’s an implementation of unidirectional data flow)

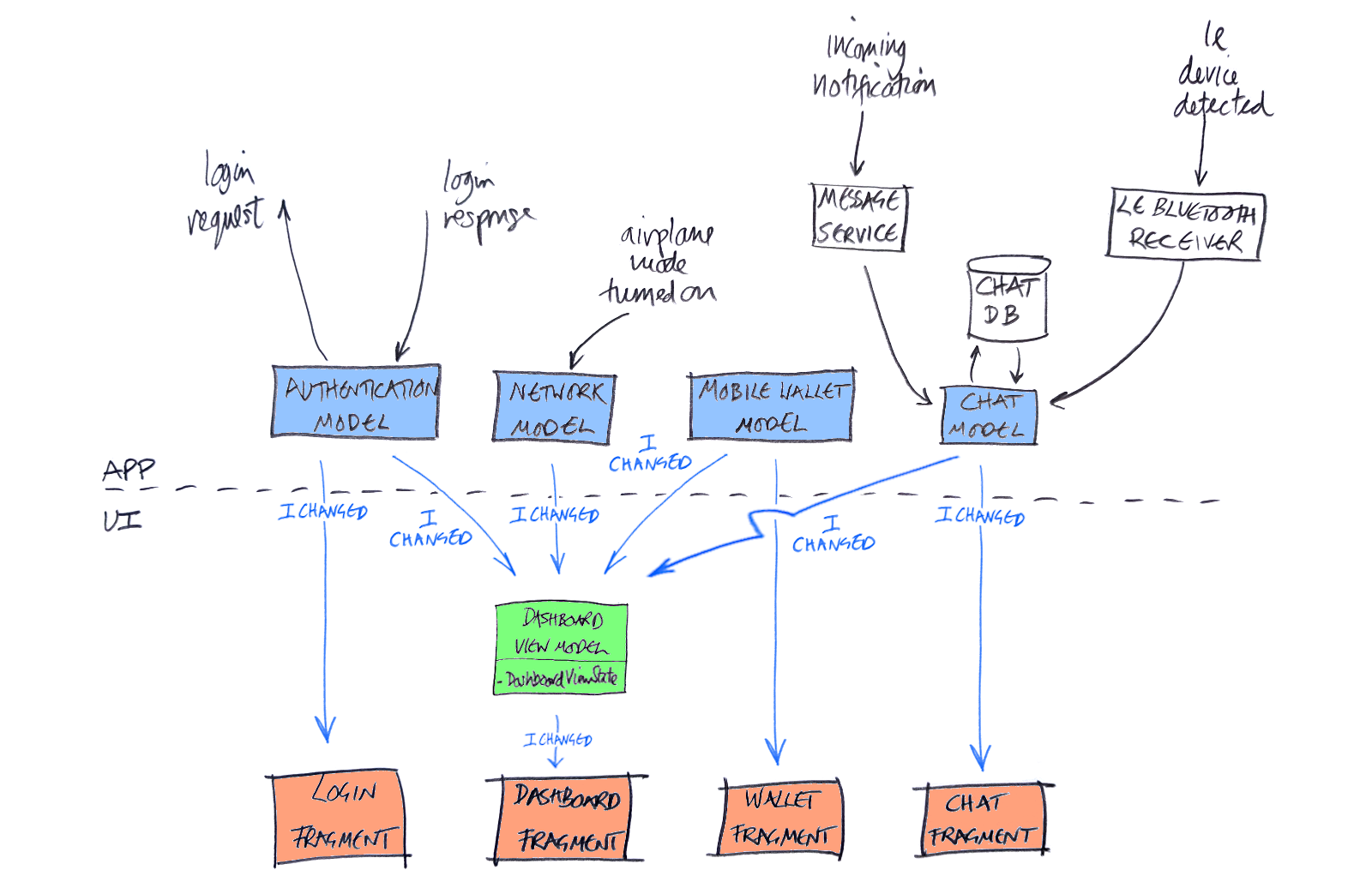

Sometimes you will want to scope a model to just a single activity (although you might be surprised at how rarely this is genuinely useful - look at how much code we removed using the MVO approach on the android architecture blueprints for example). Anyway, if you decide that’s what your app needs at that moment, use a ViewModel, give it an immutable view state, and make it observable using a fore Observable as you would with any other Model. If you are injecting your ViewModels in to the view layer and using fore observables to synchronize your UI, the view layer will not even be aware of what type of model it is anyway.

Here is where a ViewModel would fit in our example app:

The Mobile Wallet Model / Wallet Fragment section of that diagram matches what is happening in sample app 1. Here are the relevant bits of code: the observable model code and the view code that does the observing.

One great thing about MVO is that the view layer and the rest of the app are so loosely coupled, that supporting rotation already works out of the box. In the code examples above, the code just works if you rotate the screen simply because of how it’s structured - you don’t need to do a single thing.

“the code works if you rotate the screen - without you needing to do a single thing”

The code looks extremely simple and it is, but surprisingly the technique works the same if you’re using android adapters, or if you’re doing asynchronous work in your model, or fetching data from a network. This separation is also what lets us replace the UI completely with someting like Jetpack Compose by using a simple extension function.

State

We mentioned State. The fore philosophy is to manage state away from the UI layer, leaving the UI layer as thin as possible. fore puts state in the models where it can be comprehensively unit tested. For example, if you want to display a game’s score, the place to manage that state is in a GameModel. The view simply represents whatever state the GameModel has, and is synchronised everytime the (observable) GameModel changes:

public void syncView() {

pointsView.text = gameModel.getScore();

}

fun syncView() {

pointsView.text = gameModel.score

}

Notice the syncView() method does not take a parameter. It gets all it needs from the models that the view is observing. This style of view state binding is deceptively simple, and is one of the reasons that fore is so tiny and the resulting view layer code so sparse.

For Compose UIs syncView() is not even necessary, simply use fore’s observerAsState() extension function and write your state driven Compose UI code as usual

val walletState by wallet.observeAsState { wallet.state }

Send Actions to this gameModel when you need to do something like play a round: you have yourself the basics of a UDF app

Dependency arrows

If you know your MV[X]s then you’ll notice MVO has some similarity with both MVI and MVVM. As with all MV[X] architectures, with MVO the Model knows nothing about the View. When the view is destroyed and recreated, the view re-attaches itself to the model in line with the android lifecycle and re-draws the state provided to it by the model. Any click listeners or method calls as a result of user interaction are sent directly to the relevant model or an intemediary viewModel (from the UI thread - asynchronous code is managed in the models, not at the UI layer). With this architecture you remove a lot of problems around lifecycle management and handling rotations, it also turns out that the code to implement this is a lot less verbose (and it’s also very testable and scalable).

There are a few important things in MVO that allow you an architecture this simple:

- The first is a very robust but simple Observer API that lets views attach themselves to any model (or multiple models) they are interested in

- The second is the syncView() convention

- The third is writing models at an appropriate level of abstraction, something which comes with a little practice

- The fourth is making appropriate use of DI

If you totally grok those 4 things, that’s pretty much all you need to use MVO successfully, the code review guide should also come in handy as you get up to speed, or you bring your team up to speed.