Contents

Tutorials

There is a short series of dev.to tutorials which include more sample apps covering the basics of fore here

Presentations

There are a couple of presentations hosted on surge that I occasionally use, they might be useful for you too. Ironically they don’t work at all on mobile.

They were written using spectacle and reveal.js which are both pretty good javascript presentation libraries.

State vs. Event at the UI layer

Compares the two main strategies used when updating a view: using “event-y” architectures like MVP, MVC and using “state-y” architectures like MVO, MVI, MvRx.

presentation here (click “s” to view the presentation notes)

Android architecture basics

This spells out the main problem with the default android architecture and the motivation for using libraries like fore in the first place.

Presenter perspective including notes is here

Regular slides without notes is here

(if you open those two links on separate tabs of the same browser, the slides will automatically keep themselves in sync)

fore basics

This one takes you though all the main points of fore together with a lot of examples. I don’t think it really adds anything that isn’t already in these docs - it’s like a quick summary version.

Presenter perspective including notes is here

Regular slides without notes is here

(Again, if you open those two links on separate tabs of the same browser, the slides will automatically keep themselves in sync)

State versus Events

Let’s defer to this article

Android’s Original Mistake

[This is old history BTW, just here for interest]. Separating view code from everything else is widely considered a good thing, but despite that agreement, it’s still common to see android apps that write most of their code in the view layer.

Unfortunately, right from its inception the Android platform was developed with almost no consideration for data binding or for a separation between view code and testable business logic, and that legacy remains in many code bases to this day.

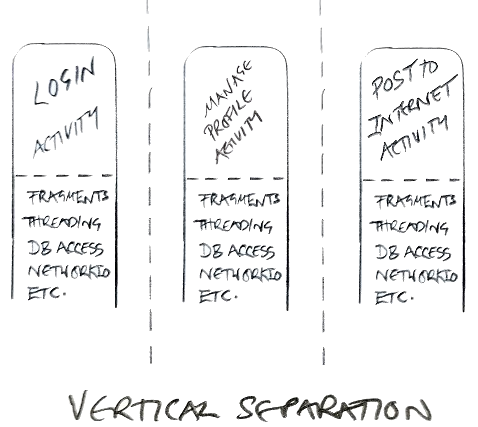

Instead of separating things horizontally in layers with views in one layer and data in another layer, the Android designers separated things vertically. Each self contained Activity (incorporating UI, data and logic) wrapped up in its own little reusable component. That’s also probably why testing was such an afterthought for years with Android - if you architect your apps like this, testing them becomes extremely difficult.

Android seems to have been envisioned a little like this:

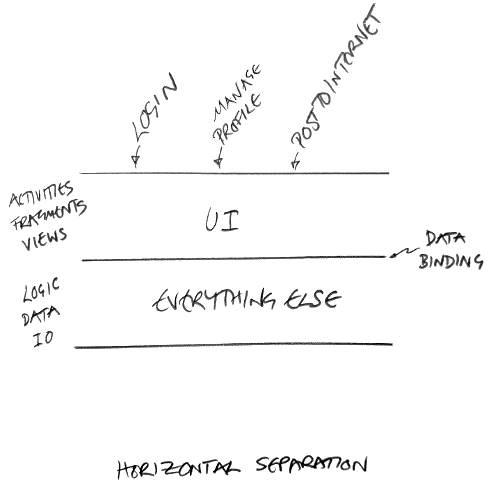

A more standard way of looking at UI frameworks would have been to do something like this:

I know, crap diagrams, but anyway a lot of the complication of Android development comes from treating the Activity class as some kind of reusable modular component and not as a thin, ephemeral view layer (which is what it really is). Hacks like onSaveInstanceState() etc, are the result of fundamentally missing the basic requirement of (all?) UI platforms: the need to separate the view layer from everything else.

Despite the obvious problems of writing networking code or maintaining non-UI state inside an ephemeral view layer, think about how many Android apps you’ve encountered that fill their Activity and Fragment classes with exactly that. And think about how much additional code is then required to deal with a simple screen rotation (or worse, how many apps simply disable screen rotation because of the extra headache). How many times have you seen similar code that exists purely to enable android’s ephemeral view components to communicate with each other? (instead of having the view components communicate with application scoped models or viewmodels, leaving the views to simply represent the current state of the app).

If you’re a new android developer the above description might not be that familiar, things did finally improve in android world when ViewModels were introduced. Although the situation hasn’t gone away, just moved to a component that has a longer lifecycle.

The fore sample apps should clearly demonstrate just how clean android code can become once you start properly separating view code from everything else.

With the advent of Compose UI, this situation changes again! As Composables replace XML layouts, they do have a mixture of data and UI in them (though hopefully not business logic).

Troubleshooting / How to Smash Code Reviews

Android apps that are written in MVO style have a certain look to them code-wise, the code in these docs and the sample apps looks very similar. This really helps when performing code reviews because structural errors tend to jump out at you a little more. The first part of this post explains the concept better than I could, and I’d recommend you give it a quick read.

Typical characteristics of an app built with fore

- The structure tends to contain two main packages (among others): features (which is usually straight forward testable code) and ui (which can only be tested with tools like Espresso or Robolectric). Examples: here, here and here

- For Clean Architecture implementations, the ui package can sometimes be called presentation and the feature package will often be renamed to domain and have its data specific components extracted and placed in a data package. It’s also common to find clean architecture layers implemented in modules, rather then just packages. See here for an example clean architecture implementation using fore

- Activity and Fragment classes tend to be very light and won’t contain a lot of code in them. They are part of the view layer after all. Examples: here, here and here

- The View classes follow a very standard flow which is: get a reference to UI components -> inject model dependencies -> setup click listeners/adapters etc -> setup any animations if needed -> make the ui reactive by adding and removing an observer and using a syncView method. There are techniques to reduce some of this boiler plate though, so that views can end up looking more like this or this

Given any app that is using fore observables to implement an MVO style architecture (clean or otherwise): first check the package/module structure, then investigate one of the activities and/or fragments to check it’s as small as it can be. Next take a look at a UI class to see if you recognise the flow mentioned above. Check the reactive behaviour especially i.e. is an observer being added and removed, how does the syncView method look. Look out for any UI state being set outside of the syncView method. It should take seconds to establish if the project is approximately correct and has a chance of the UI remaining consistent, handling rotations and not having memory leaks. Further to that, here is a list of specific warning signs that will highlight potentially incorrect code.

Common Issues

1) Code that sets view states outside of syncView(). Example: “clickListener -> { loading.visibility = View.VISIBILE …}”. That’s a very common pattern in MVP (and, amongst other things, it makes handling rotation hard). Doing that in MVO (or MVI for that matter) means short cutting the uni-directional data flow convention of: receiving state changes -> then setting your UI. The place to do that is in syncView() which gets called on any state change. If you stick to syncView(), all UI changes will happen in one place, it’ll usually require less code, and you’ll usually end up with less (or no) UI consistency bugs. Point your developers to the reactive ui section where it talks about syncView().

2) Wherever you see an addObserver() it’s always worth checking that you can see the associated removeObserver() call in the mirrored lifecycle method (eg. onStart()/onStop() or onResume()/onPause()) to make sure references are being cleaned up and memory isn’t being leaked - note that this might be hidden behind a lifecycleObserver. Like most of the advice here, this is not specific to fore (since forever on Android, any time you add and remove any kind of callback in an android UI component, it has to be done using mirrored lifecycle methods). See the recently released then quickly advised against: lifecycleScope.launchWhenStarted.

3) Any change of state in an observable model that doesn’t end with a call to notifyObservers(). Even if it’s not necessary for the current implementation, by not notifying the observers here, we now have a model that only works in certain (undocumented) circumstances. If someone else comes along and wants to observe your model and does not get a notification as expected when some state changes, something will break.

4) Code or tests that makes assumptions about the number of times syncView() or somethingChanged() will be called This is pretty important, you can’t simply fire one off events based on syncView() being called (like starting an activity for example) - because you are depending on being notified by the model an exact number of times. Code like that can easily break in two ways:

- 1) If the model is later refactored to contain some other piece of state that changes, it will result in an additional notification, and therefore call to syncView(), that your view was not prepared for.

- 2) If the view is later refactored to observe an additional model, that additional model will also notify when its state changes, and you will get more syncView() calls than you were prepared for.

The deal is that whenever something (anything) changes in a model, you will be notified. But you maybe be notified more than you expect. In order to be robust, your syncView() must make no assumptions about the number of times it may or may not be called. Sometimes you will of course need to bridge the world of syncing views and triggering one off events, and the way you do that in fore is to use a Trigger.

Occasional Issues

5) Activities and Fragments that have anything in them (other than the standard flow of a UI layer component). Sometimes there are good reasons for putting code in Activities and Fragments, setting up bundles and intents is often unavoidable for example, but you should be immediately suspicious of any errant code that gets into these classes. Often this code can be moved to a model class, safely away from tricky lifecycle issues and where it can also be more easily tested. It’s generally helpful to avoid any having asynchronous or networking code in your Activity or Fragment code at all, unless there is a very good reason for it.

6) Views talking to other Views, even one view asking for the other view’s state. Sometimes this takes the form of a Fragment casting its parent activity and then calling that activity for further processing or information (unfortunately that’s a very common pattern which has occasionally been promoted by Google). Generally if you have two ephemeral view layer components talking to each other, it’s going to cause all sorts of edge case issues. Keep the view layer thin, put that logic or state in a model, inject that model into the view components and let the view components access it directly. That totally removes the dependence on host Activities or other views and removes a lot of boiler plate in the process.

7) Adding or removing observers outside of android lifecycle methods. I’m not saying there is never a good reason to do that (particularly if you want to set up one long living model to observe the state of another long living model). But it is a bit unusual and might warrant a rethink. It’s usually a mistake (and a cause of memory leaks).

8) Any getter method or kotlin property that does more than pass back an in-memory copy of the data asked for. In order for the reactive UI to be performant, we want any getter methods to return fairly quickly. Try to front load any processing rather than doing it in the getters.

9) Any observers that do anything other than sync their entire view are usually (but not always) incorrect. Generally the observer just does one thing (sync the view), and this means you can use the same instance of that observer to register with several different models in the same view.

10) A syncView() that is more than 5-15 lines long and/or doesn’t have one line to set an affirmative value for each property of each UI element you are concerned with. Take a look at how to write a good syncView() method.

11) Any click listeners or text change listeners should generally be talking directly to model classes, or asking for navigation operations for example: MyActivity.startMe(getContext()). Occasionally it’s useful for listeners to directly call syncView() to refresh the view (when an edit text field has changed for example). What they generally shouldn’t be doing is accessing other view components like fragments or activities and checking their state in some way. Sometimes if you follow this code it ends up calling a model class somewhere down the line anyway, in which case the model class should just be called directly (you get your model references to any view class using dependency injection)

12) Public methods on models that return their state directly through a callback, and therefore shortcut the MVO pattern. Depending on what data is returned here, this may make it difficult to cleanly support rotation. It might be worth re-reading the MVO architecture page and the reactive UIs page.

13) Any state kept in view layer classes is at risk of being lost. How does this view survive rotation, would loosing that state matter? if yes, then it might be better kept inside a model away from the view layer, or in a ViewModel

14) Any logic kept in view layer classes is usually harder to test. It can be hard to totally remove all the logic from the view layer (especially navigational logic once you factor in the back button) but be aware that the logic here is usually a lot harder to test and if you can move it away from the view layer reasonably easily, then you probably should. If there is some particularly complicated logic for a view state in the syncView() method for example, that logic is a prime candidate to be moved out of the view layer into a model or utility class where it can be tested more easily.

15) Having a syncView() method, but not calling it syncView(). This specific method is talked about a lot and it’s very handy to call it the same thing so that everyone knows what everyone else is talking about. Making your View (Activity or Fragment) implement SyncableView is probably a good idea anyway (and will let you take advantage of the LifecycleObserver to remove even more boiler plate).

16) Exposing non UI thread behaviour from a model. Any state we expose from a model should always be the truth, and that’s easier to guarantee if we only update our state and notify our observers on the UI thread. This is natural when using legacy call back APIs from within a model (for example, to make a network call on an IO thread) as the callback usually arrives back on the UI thread. But with coroutines you are responsible for switching back to the UI thread once your suspend function has returned. See here for an example.

Dependency Injection Basics

Dependency Injection is pretty important, without it I’m not sure how you could write a properly tested Android app. But it’s not actually that complicated.

All it really means is instead of instantiating the things that you need to use (dependencies) inside of the class that you’re currently in, pass them to your class instead (either via the constructor or some other method if the constructor is not available such as with the Android UI classes).

Don’t do this:

public MessageSender() {

networkAccess = new NetworkAccess();

}

fun MessageSender() {

networkAccess = NetworkAccess()

}

Do this instead

public MessageSender(NetworkAccess networkAccess) {

this.networkAccess = networkAccess;

}

fun MessageSender(networkAccess: NetworkAccess) {

this.networkAccess = networkAccess

}

If you don’t have access to the constructor, you can do this (like we do in a lot of the fore sample apps):

MessageSender messageSender;

protected void onFinishInflate() {

super.onFinishInflate();

messageSender = OG.get(MessageSender.class);

}

private lateinit var messageSender: MessageSender

override fun onFinishInflate() {

super.onFinishInflate()

messageSender = OG[MessageSender::class.java]

}

In a commercial app, the number of dependencies you need to keep track of can sometimes get pretty large, so some people use a library like Dagger2 to manage this:

@Inject MessageSender messageSender;

protected void onFinishInflate() {

super.onFinishInflate();

DaggerComponent.inject(this);

}

private lateinit var messageSender: MessageSender

override fun onFinishInflate() {

super.onFinishInflate()

DaggerComponent.inject(this)

}

The main reason for all of this is that dependency injection enables you to swap out that NetworkAccess dependency (or swap out MessageSender) in different situations.

Maybe you want to swap in a mock NetworkAccess for a test so that it doesn’t actually connect to the network when you run the test. If NetworkAccess is an interface, dependency injection would let you replace the entire implementation with another one without having to alter the rest of your code.

A quick way to check how your Java code is doing on this front is to look for the keyword new (it’s slightly less obvious in Kotlin as there is no new keyword). If you are instantiating an object, then that is a dependency that won’t be able to be swapped or mocked out at a later date (which may be fine, as long as you are aware of it).

Incidentally don’t let anyone tell you that you must use a dependency injection framework in your android app. In the fore sample apps, all the dependencies are managed in the OG(ObjectGraph) class and managing even 100 dependencies in there is no big deal (if you have a mobile app with more than 100 global scope dependencies then it’s possible you’re doing something wrong anyway). Keeping them all in the same place also lets you see what your dependency graph actually looks like at a glance. So if you and your team dig dagger, then use it. But if you spent a few days stabbing yourself in the eye with it instead - feel free to manage those dependencies yourself. See here for more on this

Inversion of Control

This term really confused me when I first heard it years ago, so here’s my take in case it’s helpful for you or your team.

Imagine if we have a company. It has a CEO at the top. Underneath the CEO are departments like Marketing, HR, Finance. Those departments all print documents using a printer.

The CEO is in control of the whole lot, whatever she says goes. But if you took that to extremes it would be ridiculous. The CEO would tell the departments exactly what documents to print, but also with what paper, and what printer ink. When paper tray 3 ran out, the CEO would be the one to decide to switch to using paper tray 2 instead, or to display an error on the printer display. After 5 minutes of no printing, the CEO would decide to put the printer into power saving mode. You get the idea. Don’t write software like that.

Inversion of control means turning that control on its head and giving it to the lower parts of the system. Who decides when to enter power saving mode on the printer? the printer does, it has control. And the printer wasn’t manufactured in the office, it was made elsewhere and “injected” into the office by being delivered. Sometimes it gets swapped out for a newer model that prints more reliably. Write software like that.

Syncing the whole view feels wasteful, I’m just going to update the UI components that have changed for efficiency reasons.

This seems to be the reaction of about 20% of the developers that come across this pattern for the first time. I think it might depend on what style of development experience they have have had in the past (it obviously won’t be a problem for anyone coming from MVI for example).

The first thing to bare in mind is of course: “premature optimisation is the route of all evil” or however that quote goes.

The second thing is to make absolutely sure there is a complete understanding of the dev.to spot the bug tutorial.

Everything in computing is a trade off, and when considering a trade off you need to understand two things: the upsides (in this case: the lure of only updating the parts of the view that need updating) and the downsides (in this case: loosing the ability to support rotations by default, and increasing the risk of UI consistency issues as discussed in the tutorial above).

Making a tradeoff when you don’t fully appreciate one of those sides (up or down) is obviously not a great place to be.

If after appreciating the downsides of this tradeoff, there is still an interest in sacrificing that robustness in the name of “performance” or “battery life”, then read on.

This is not usually a problem for any developer that has written game loops, or implemented their own animations using easing equations or similar, but if you’ve never done that type of development, you might be in danger of seriously underestimating how fast even the most basic android phone runs.

In to the matrix

Before we go any further, if you haven’t already, go to developer settings on android and check out the debug tools that let you see the screen updates as they happen.

WARNING if you’re epileptic, maybe skip this part, you will see some incredibly annoying rapid screen flashing as the screen is updated multiple times a second. I’m not epileptic but a few minutes of that makes me feel seriously car sick.

The first one is “Show surface updates” it flashes when part of the screen is being redrawn. You might be surprised just how often the screen is being updated as you use your android device.

The second option you have is “Show GPU view updates” this only shows GPU updates and depending on your device you may see this working a lot, or not at all.

Now that you’ve peeked a little under the hood, you’ll be able to appreciate that if you’re looking at a single waiting animation (like a standard indeterminate progress bar on Android), the screen (or at least that part of it) will be updating the UI around 30 times a second in response to a ui widget that is continually recalculating its state, also 30 times a second. Any scrolling of a list view; any background blurring animation; even a blinking cursor will sometimes cause the screen to be redrawn 30 times a second or so. That’s how fast it needs to be to trick human eyes into thinking something is moving when it isn’t - you’re just seeing a sequence of still images.

If you put some logs in the syncView() method you’ll also see that it is in fact hardly called at all most of the time, unless you are using the Observables to run an animation loop (which is something that you absolutely can do given the performance of the observer implementation in this library by the way).

The syncView() also completes pretty quickly as all of your getters should be returning fast anyway, as recommended here.

In addition, if you are setting a value on a UI element that is the same as the value it already has, it would be a bug in the android framework if it caused a complete re-layout in response anyway (I’m not guaranteeing such bugs don’t exist, in fact EditText does something slightly stupid: it calls afterTextChanged() even when the text is identical to what it had before, but it’s easy to work around. In any case, if you ever did get any kind of performance issues here, that’s the time to measure and see what is happening, not before). If you follow the guidelines here correctly you will almost certainly encounter no problems at all, and that includes running on very cheap, low end devices (it wasn’t an issue 10 years ago, it’s certainly not an issue now). What you do get however is unparalleled robustness and clarity of code - which, because logic mistakes become fewer under those circumstances, sometimes results in even more performant code.

If you have a model that is changing in some way that an observer just so happens NOT be interested in, you will end up making a pass through syncView() unnecessarily (but still not actually redrawing the screen): chillax and be happy with the knowledge that your UI is definitely consistent ;)